EARLY HISTORY & ORIGINS

The complex history of Scotland’s feudal baronage raises the important question of what a barony is.

If the reader requires a simple answer it is that a barony has never been just one static thing throughout history. As with the land, people and nation of Scotland they have evolved over time with differences in formal existence and practical powers. Today’s barony is much different from that of three hundred years ago, which, in turn, was distinct from three hundred years before that. A barony has also meant different things to different people. Some barons resided in their barony lands and ruled their people intimately through their court, others held many baronies and delegated management to trusted servants while they operated on the national stage. Many baronies were held onto fiercely by families for centuries, while others were frequently lost to debt, warfare or an unhappy monarch. No two baronies are the same, and that is part of their enduring interest. They have been subject to significant and sudden change but also to slow adaptations over centuries.

The story told here is a sense of this history; readers are encouraged to discover the full richness for themselves.

ORIGINS

As with anything of such great antiquity, there is no single date for the origin of Scottish feudal baronies.

We cannot trace them to one moment partly because so little documentary evidence survives from the period of their early development. There is also something in the nature of the baronage that calls to the most basic forms of human organisation. There were certainly entities resembling baronies ever since the early people of Scotland first offered allegiance to strong men who became local rulers.

The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalism in which the patriarch held his country “under God”, and partly from the later feudal system… in which the territory came to be held “of and under” the King (i.e. “head of the kindred”) in an organised parental realm. [1]

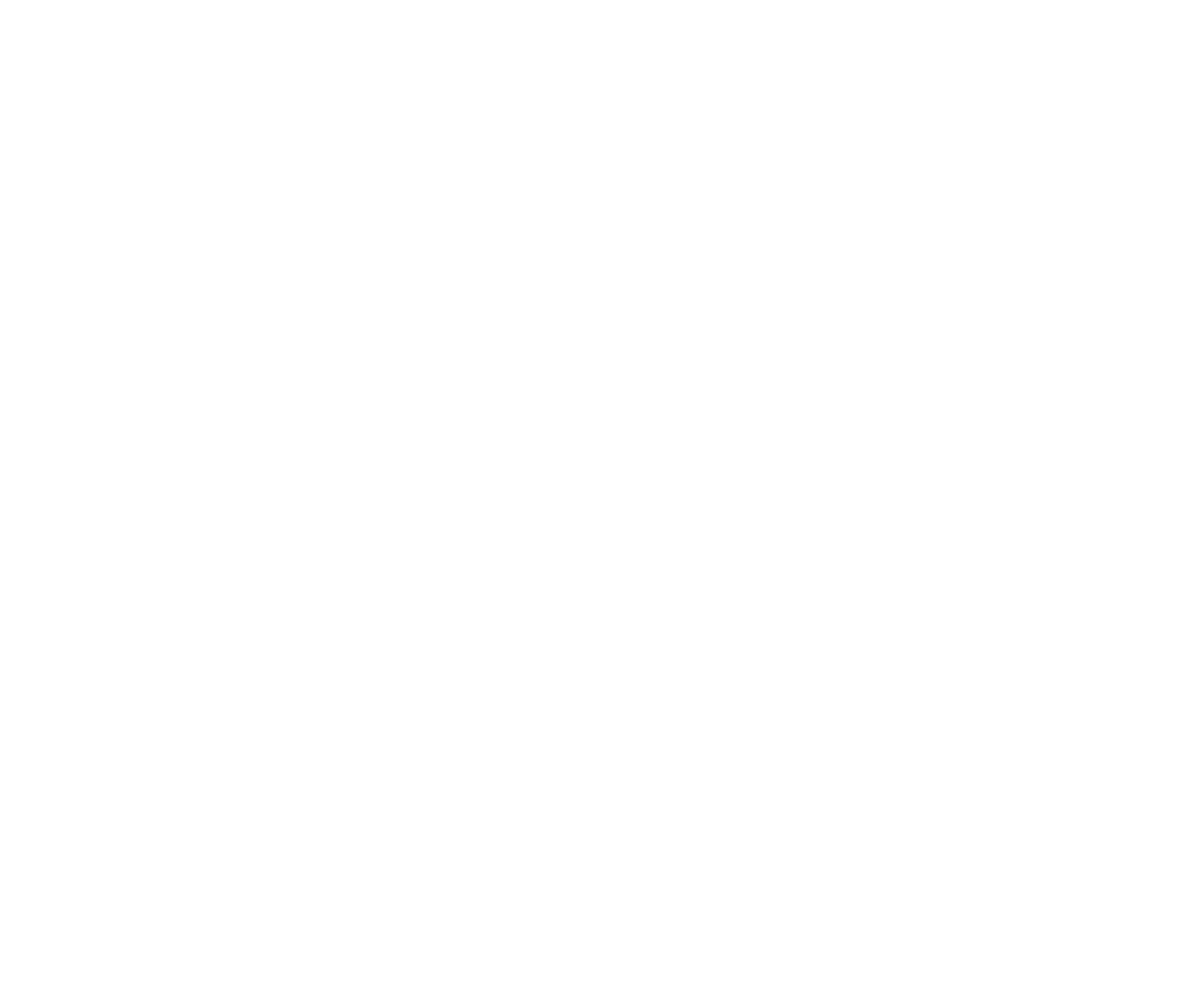

Figure 1: Map: ‘Scotiae Regnum’ South of Scotland 1595 (Ex Mercator) | National Galleries of Scotland. Unknown artist.

Moving into recorded history we find the existence of parcels of land ruled with some degree of autonomy. In the first millennium AD the Gaelic and Pictish rulers in what is now Scotland rewarded subjects with areas of the land in return for service and loyalty. Around the eleventh century the kingdom known as Alba or Scotland was ruled over directly by the Crown or by powerful regional mormaers, or earls. Kings and earls designated ‘thanes’ to run parts of their estates, which came to be called ‘thanages’. This term and system appear to have been borrowed from the Saxons ruling in southern Scotland and England.

[1] Thomas Innes of Learney and Kinnairdy, F.S.A.Scot., Lord Lyon King of Arms, ‘The robes of the feudal baronage of Scotland’ in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Vol. 79 (1944). 111.

It is from this system the feudal baronage developed, resting upon the society that was already in place.

In the early twelfth century King David I invited men of Norman and Flemish descent to Scotland to fight for him. In return they were rewarded with land and status. The name ‘baron’ is itself an Old French term for an important man. Therefore, there was not just an influx of men and a resettling of land but a deeper change in the fabric of society. It is in this period we see the feudal system instigated in Scotland, establishing a hierarchical rule over people and land.

This system is well described by the historian Bruce Durie:

At first feudal earldoms and baronies were held from the Crown by military service, requiring a specified number of knights for a defined period (normally forty days) when requested…[Earls and barons in turn] sub-feued part of their lands to these knights, held of them by knight’s service (knights’ fees), and the knights might in turn sub-feu parts of these lands to other vassals, as husbandmen (tenant farmers) and so in an a hierarchy down to the final vassals, who might have serfs and others to work the land.[2]

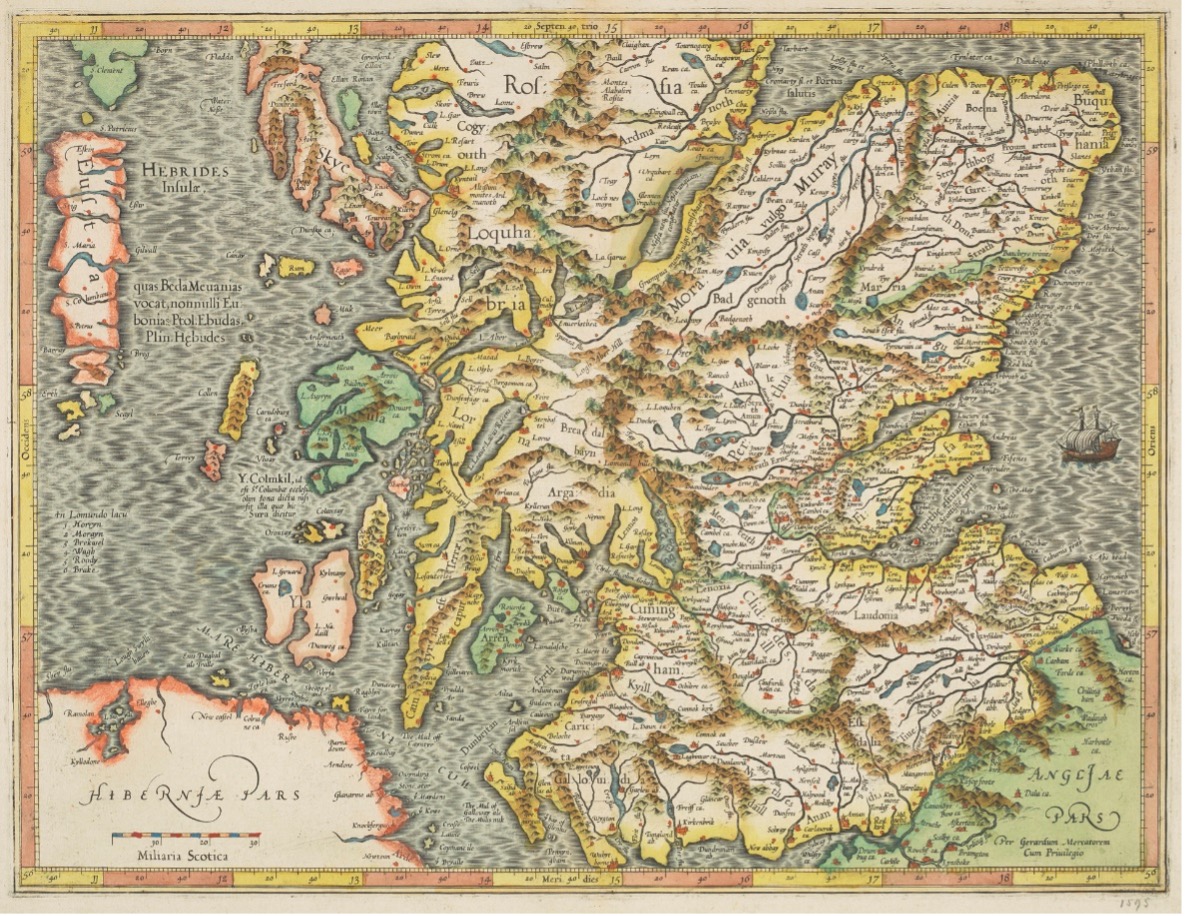

Figure 2: A Medieval Battle | National Galleries of Scotland. Robert Smirke.

In return, those who received land owed their feudal superior a form of service such as through farming their lord’s land, presenting goods or providing military assistance. While this is often considered a military system, it was primarily a ‘familial and economic’ one, and over time forms of service were increasingly replaced by payment of teinds in the form of produce or money.[3]

[2] Bruce Durie, Scottish Genealogy (Brimscombe Port: The History Press, 2015). 143

[3] Durie, Scottish Genealogy. 129; Innes of Learney, ‘The robes of the feudal baronage of Scotland’. 112.

Very quickly the feudal system proved immensely popular in Scotland and ‘took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions’.[4]

By granting this land the king expected service but also that his earls and barons ‘would rule, administer, dispense justice and generally look after that land in the sovereign’s stead’.[5] The nominal centre of the land granted as a barony was the ‘caput’ or ‘head place’, usually a building such as a castle.

Many of the new men that King David I and his successors Malcolm IV and William I brought in were granted land in the feudal system. This land was either taken out of their own Royal possessions or from estates forfeited into Crown hands. Many of the older powerful lords were brought into the system, such as the earls, successors of the great provincial mormaers.

Figure 3: David I, 1108 – 1153. King of Scots | National Galleries of Scotland. Alexander Bannerman.

In addition to baronies the feudal baronage also came to include a small number of lordships and an even smaller number of earldoms containing vast swathes of land. The thanages remained also, and until the fourteenth century existed alongside baronies until most of them became baronies themselves.[6] In a long process over the twelfth and thirteenth centuries much of Scotland became ‘feudalised’ and baronies came to ‘dominate the localities’.[7]

[4] Thomas Innes of Learney, Tartans of the Clans and Families of Scotland (Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston, 1938). 15, 25, 36.

[5] Durie, Scottish Genealogy. 139.

[6] Alexander Grant, ‘Franchises North of the Border: Baronies and regalities in medieval Scotland’ in Liberties and Identities in the Medieval British Isles, (ed.) Michael Prestwich (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2008). 181-2.

[7] Grant, ‘Franchises North of the Border’. 185-6.